Conservation Basics: An Elephant in the Forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Rainforest Trust’s work to protect habitats for threatened species is grounded in cutting-edge conservation science. But in this series, we explore the basics of conservation science and how they inform Rainforest Trust’s scientists.

Here at Rainforest Trust, we use data – a lot of data – to conserve habitats for endangered species. We need to know where the species lives, how many of them there are and how best to conserve said species.

But that knowledge is always changing. Our Rainforest Trust scientists are constantly reflecting on the central question: How do we determine the most effective strategies for conservation when we can’t be certain of everything that might affect those strategies?

We use the power of collective knowledge to overcome uncertainty. A vague concept, I know. But let me explain. Take, for example, the case of the Congo’s elephants.

Somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is an elephant. At the moment I write this piece, the elephant – the specific individual – might be sleeping. It might be eating, drinking, cavorting with another elephant or partaking in whatever other activity a wild elephant in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo might partake in.

I don’t know where, exactly, the elephant is at this precise moment or if any other elephants are nearby. I don’t know if the elephant is sick, well-fed, hungry, stressed or relaxed. I know nothing about this specific elephant. But I know an elephant is somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

African Forest Elephants. Photo by Caroline Granycome/Flickr

As a society, we know elephants are somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since we, as a species (humans), know an elephant exists somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, I, as an individual, know an elephant exists somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And now I’ve told you. So now you know.

We can infer facts about the elephant based on general trends, but with less certainty. We know what it (probably) eats. We know how big it will (probably) become. We know how old it will (probably) grow to be. We know the individual is an African Forest Elephant, as opposed to an African Bush Elephant (although African Bush Elephants live in the DRC, too, we’ll assume I’m writing about an African Forest Elephant), but we aren’t sure if that distinction is between a species or a subspecies.

There are other tidbits of information we probably don’t know. We probably don’t know where this elephant was born. We probably don’t know what other elephants this elephant has encountered. We probably don’t know how far this elephant has travelled in the past two weeks. We may know these things, but we probably don’t.

Finally, there are some details we definitely don’t know. We don’t know if this elephant has a recurring itch on its left ear. We don’t know where this elephant will go tomorrow. We don’t know when or how this elephant will die.

Science is both fueled and limited by uncertainty. Science discovers the undiscovered, sees the unseen and recognizes the unrecognizable. But science requires certainty to move forward, state assumptions and take the next step. In conservation, science necessitates action and action necessitates science. But if we don’t know everything, how can we do anything useful? Uncertainty can be paralyzing, but paralysis is unacceptable because conservation inaction leads to extinction.

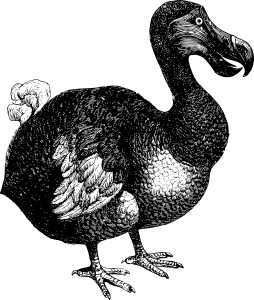

I couldn’t find any photographs of the Dodo. Because extinction is permanent.

And extinction is permanent.

As conservation grew – from a pastime to a field of study to an industry – the science and conversation around it only grew more and more complicated. This was good! The sharing of ideas, knowledge and inquiries, discussions at conferences, community meetings and camping trips, newly published papers, books and films, and policy, law, economics, biology, chemistry, geology, geography and fashion all add to the field of conservation. Every one of these methods is useful and inspiring, but not always global or continuous.

But these developments also meant that conservation science became more and more complicated. So as conservation grew – from a pastime to a field of study to an industry – fewer and fewer people were fully in the know.

We’re going to change that.

It’s completely understandable if you don’t understand the nuances of the science and policy of wildlife conservation. But I bet you know animals exist. You probably know some species are endangered and some species are not. You probably don’t know every step in the decision-making process, or who decides what is Endangered or Vulnerable or of Least Concern. You definitely don’t know how to save every species. But we need to find the solutions to protect every species on the planet. Not only pandas, lions and bees, but every moth, tree, fungus, protozoan, sea cucumber and anglerfish needs our help. Every. Single. Species.

And you (that’s right, you) play an important role in getting that done.

The conservation community can’t save the planet on our own. We don’t have the necessary time or capacity to protect every species of spider, let alone every species. So you have two options. You can take the route leading to a hilarious yet meaningful memoir the New York Times Book Review will call “surprisingly refreshing and heartfelt” and quit your job, move to Alaska and hand-rear orphaned caribou to release to the wild. If you think that’s your calling, by all means, please do so. But you don’t need to and I actually encourage you not to.

We need bankers, writers, factory workers, farmers, lawyers, politicians, air traffic control officers, grocery store clerks, retirees, students, actors, Olympic speed skaters, plumbers, recreational golfers, Yankees fans, Red Sox fans, people who don’t like baseball, people who’ve never heard of baseball, people who have heard of baseball but don’t feel one way or the other about baseball and everyone else to be aboard the Biodiversity Express. Stay where you are, keep doing what you’re doing and keep conservation in mind. By learning a little more about how conservation works, you might end up with a bigger appreciation of how important conservation is.

Look at all those potential conservationists!

I’m going to help you start doing that by unraveling some of the nitty-gritty. This series will explore how Rainforest Trust uses conservation science and everything it entails. We have big plans for conservation and want you all to understand exactly why our work is vital. I, on your behalf, will ask little questions to get to the bottom of the big questions: Who does the research? What information do we need to assess species status? Where does the Black-bellied Pangolin live? When did the Yangtze River Dolphin become functionally extinct? Why is the Giant Panda no longer listed as Endangered? Why should you care? How are we at Rainforest Trust using this information to protect our planet’s species?

Science is about uncertainty, but uncertainty does not consume science, nor does it immobilize it. (See Appendix I of the official IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, titled “Uncertainty.”) We need not know every detail to save our planet. We only need to keep learning.

We need you to be an advocate for conservation. But that starts with a foundation of understanding. So let’s begin with the knowledge that somewhere in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is an elephant.